The spread of Covid-19 is creating a chain reaction of economic effects. The initial outbreak in China, which probably began in December but was not acknowledged until late January, led to public health measures which caused workers to stay away from work, travelers to stop traveling, and consumers to stay away from shops, restaurants and entertainment venues. Coal consumption fell 40% as factories were shut down. Supply chains that depend upon Chinese manufactured goods were interrupted. Shipping volumes dropped sharply.

Economists have been scrambling to monitor the contraction in economic activity. In the early days, many economists suggested the the impact would be minor, merely causing a slowdown in China's economic growth in 1Q19 that would be fully made up in a V-shaped bounce back in 2Q19. However, as February wore on, it became abundantly clear that the virus had not been contained. Outbreaks in other countries including Japan and South Korea, on passenger ships, and eventually further afield in Iran and Italy made it clear that Covid-19 had become a pandemic, even if the World Health Organization was reluctant to say so. Now, economic activity has stalled in Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo, Seoul and Milan. Countries around the world are warning their citizens to prepare for Covid-19 outbreaks. In Canada, the federal health minister has suggested that citizens put together survival kits to see them through the possibility of two weeks or more of self-imposed quarantine.

As time has passed, economists have progressively cut their forecasts for 2020 economic growth and in many cases have acknowledged that a V-shaped rebound in 2Q19 is becoming much less likely as the virus continues to spread internationally.

The Bank of Canada's Dilemma

In January, Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz revealed that the Bank's forecast for growth of Canada's real GDP in 4Q19 had been cut to 0.3% at an annual rate from the October forecast of 1.7%. The Bank projected a modest rebound in 1Q20 growth to 1.3% and to about 2% in subsequent quarters of 2020. In releasing these projections along with a decision to leave the policy rate unchanged at 1.75%, Governor Poloz said,

All things considered, then, it was Governing Council’s view that the balance of risks does not warrant lower interest rates at this time. In forming this view, we weighed the risk that inflation could fall short of target against the risk that a lower interest rate path would lead to higher financial vulnerabilities, which could make it even more difficult to attain the inflation target further down the road. Clearly, this balance can change over time as the data evolve. In this regard, Governing Council will be watching closely to see if the recent slowdown in growth is more persistent than forecast. In assessing incoming data, the Bank will be paying particular attention to developments in consumer spending, the housing market and business investment.Since making this statement, real GDP growth in 4Q19 did match the BoC's anemic projection of 0.3% at an annual rate. Early data for 1Q20 has been mixed with housing starts, real exports and total employment modestly firmer in January but with total hours worked, the manufacturing PMI and real imports all down from the 4Q19 average. Activity levels in February will have been depressed by the rail and port blockades by activists protesting the Coastal Gas Link Pipeline.

Global growth forecasts for 1Q20 have been progressively marked down over the past few weeks as the spread of Covid-19 moved quickly and became an incipient pandemic that was likely to last longer and deal a bigger blow to global activity than originally thought.

If the Bank of Canada was worried in mid-January, before the Covid-19 pandemic began, that the late-2019 slowdown in growth might be more persistent, there can be no doubt that the downside risks to both growth and inflation have increased substantially since then.

Why the BoC should be easing

Even before the spread of Covid-19 and the precautionary actions that are slowing global commerce, there was strong reason for the Bank of Canada to follow the lead of the US Fed and numerous other central banks since mid-2019 in cutting their policy rates.

Since early May 2018, Canada's commodity prices have been falling. When commodity prices fall, Canada's terms of trade weaken as the prices of our exports fall relative to the price of our imports. Historically, the Bank of Canada has responded to sharp falls in commodity prices and the terms of trade by easing monetary conditions through a combination of lowering the policy rate and allowing the Canadian dollar to weaken against foreign currencies. The Bank last did this in early 2015 when crude oil prices collapsed.

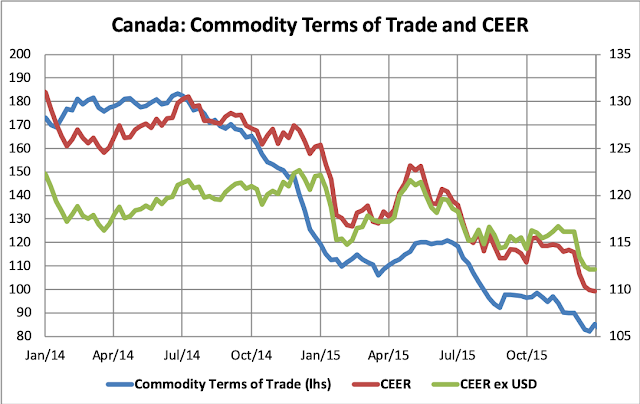

In the chart below, for the 2014-15 period, the commodity terms of trade, which I define as the Bank of Canada's commodity price index divided by the core CPI, is shown alongside the BoC's measure of Canada's nominal effective exchange rate (CEER). The CEER is shown against all currencies and also against all currencies excluding the US dollar.

As the chart clearly shows, the commodity terms of trade dropped sharply in late 2014 as world and Canadian crude oil prices collapsed. As this occurred, Canada's effective exchange rate weakened because of a weakening of the Canadian dollar versus the US dollar, while excluding the USD, the effective exchange rate actually strengthened until January 2015. In January, the Bank of Canada stunned market participants by cutting the policy rate, which triggered a sharp fall in the effective exchange rate, both including and excluding the USD. The weakening of the CAD helped cushion the blow of the oil price collapse on oil-producing regions of Canada and helped improve the export competitiveness of other sectors and regions of the economy.

Now look at the same chart for the 2018-20 period.

Once again, the commodity terms of trade peaked in May 2018 before falling sharply in late 2018 as central bank tightening, led by the US Fed, raised recession fears. Slowing growth and the sharp fall in commodity prices, along with a melt-down of global equity markets, caused the Fed and other major central banks to reverse course by cutting their policy rates and, in some cases, adding liquidity by expanding their balance sheets through quantitative easing. The Bank of Canada was an outlier, choosing not to follow suit with rate cuts of its own. The result was that, despite a sharp weakening in commodity prices, Canada's nominal effective exchange rate appreciated. This not only made times more difficult for commodity producing sectors and regions, but also caused a deterioration in the export competitiveness of Canada's manufacturing exports at a time of stagnating global trade. The Bank of Canada, through this period, expressed concern about the risk that high household debt levels posed to financial stability. The BoC made a clear trade-off, attempting to constrain household borrowing, especially mortgage borrowing in Toronto and Vancouver, at the expense of Canada's commodity sector and other export oriented industries.

Since the onset of Covid-19, commodity prices have renewed their decline. The commodity terms of trade have now weakened 27.5% since May 2018, half of the steep decline in 2014-15. The 2014-15, the 52% decline in the commodity terms of trade was cushioned by a depreciation of 22% against the USD, a depreciation of the nominal effective exchange rate of 15%, and an effective depreciation of 7.5% against non-US trading partners. The 27.5% decline of the commodity terms of trade since May 2018 has been accompanied by just a 1.6% depreciation against USD, but a 1.6% appreciation in the nominal effective exchange rate, providing no relief for commodity producers and a deterioration in the competitiveness of other exporters. Alberta, Saskatchewan, Northern BC and Newfoundland are suffering not only from weak commodity prices and regulatory strangulation, but also from a strong exchange rate generated by the BoC's unwillingness to cut the policy rate. Auto plants in Ontario are closing or laying off workers as Canada's competitiveness weakens.

We are just now beginning to see the economic impact of Covid-19. Purchasing managers' surveys showed activity levels collapsed in both the manufacturing and services sectors in China. Declines are also likely to be recorded in Japan, Korea and other Asian countries in February. Measures now being taken in Europe and the United States suggest that as the virus spreads, so too will the economic weakness.

Here in Canada, where hard economic data is published with a lag of up to six weeks relative to the United States, it would be foolish to wait for statistical evidence for the BoC to take action and cut the policy rate. Even without Covid-19, the failure to cut policy rates along with other major central banks has slowed growth and done so at the expense of the weakest sectors and regions of the country.

No comments:

Post a Comment