This is a follow-up on my post, Canada Post Covid19, from March 31. I concluded that post with the following:

Bank of Canada Governor Poloz said that the lowered private sector forecasts he was seeing were little more than arithmetic and promised to unveil new projections on April 15th from the Bank of Canada's forecasting team, which he described as "the best there is". He suggested that more than just doing arithmetic, the Bank of Canada's forecasters would take account of confidence effects and how behavior might change in the post-Covid19 world. One suspects that the Bank will provide a range of scenarios based on differing assumptions about the course of the Covid19 pandemic and the likely economic repercussions of a shorter or longer crisis.

Many questions are not answered, or even addressed, in these forecast revisions. Will government support programs and a huge increase in deficit spending prevent corporate defaults and a permanent destruction of economic capacity. If debt defaults are too large, will that tigger persistent higher unemployment and unleash deflationary forces? Will Canada's highly productive energy industry be able to recover when government policies are tilted toward "phasing out" fossil fuels? Will financial markets take in stride the coming huge spike in Canada's federal debt-to-GDP ratio, or will investors demand a higher credit risk premium for a country which already has very high levels of household and corporate debt? Will the Bank of Canada's policy interest rate setting stay at the effective lower bound indefinitely, and if so, will bond markets anticipate higher inflation and bond yields? Perhaps the Bank of Canada's crack forecasting team will shed some light on these questions. But probably not.

Having read the Bank of Canada's April Monetary Policy Report, I must admit that I am not surprised that most of the questions posed above were not addressed. As noted in the MPR, the future course of Covid19 is still too uncertain to make projections with any precision. As I suspected, the BoC chose to provide a range of scenarios based on differing assumptions about the course of the pandemic and the eventual relaxation of containment measures. I was surprised, however that while the MPR did provide charts showing a range of plausible projections for the level of real GDP and CPI inflation, it did not provide any numerical projections.

However, from the charts provided by the MPR, we can extract the Bank's most optimistic and most pessimistic projections and they are very surprising.

First, a digression. When I started my career as an economist straight out of graduate school in 1977, I went to work at The Conference Board of Canada. At the time, the Conference Board had Canada's only private sector quarterly econometric model forecast. The Board had a very strong team of forecasters and its' quarterly forecasts were presented at large conferences for members, quite often with up-and-coming economists from the Bank of Canada in attendance. I worked at the Board from 1977 to 1980, helping out with the forecast and publishing a number of research reports. These forecasts and research reports had lots of charts and graphs. We had a big mainframe computer that could print out the tables with all of the forecast numbers, but computer graphic printers had not yet been perfected. Instead, we had a chart room, which employed numerous graphic artists who toiled all day grinding out the charts using graph paper, rulers, light tables and all the many tools of their trade. Remembering those days, one can use a ruler and a pencil and reverse engineer the Bank of Canada's charts in the MPR to come up with the data points for their most optimistic and pessimistic scenarios.

When one goes to the trouble to do that, one gets a surprise, as shown in the chart below. In the chart, I compare the BoC's projections with the pre-Covid19 path of potential GDP and with forecasts made in late March by TD Economic Research and by the Parliamentary Budget Office which were shown in my previous post.

The surprising thing about the BoC projections is that even the Optimistic projection shows a far deeper plunge in real GDP in the first half of 2020 than the worst private sector forecasts. In the MPR press conference Governor Poloz said that he thought the Optimistic projection was attainable if containment measures started being relaxed in late May or early June. The Pessimistic projection, which contemplates a later relaxation of containment measures, shows the level of real GDP collapsing by more than three times as much as either the worst private sector forecast or the forecast used by the Parliamentary Budget Office when it projected a C$182 billion deficit for FY2020-21.

The BoC's Optimistic real GDP projection works out to be a contraction of about 6.5% in 2020 followed by about a rebound to about 8.5% growth in 2021. The average forecast from the economists of Canada's big banks in early April was for a contraction of about 4% in 2020 followed by a slightly better than 4% rebound in 2021. For comparison, the latest IMF forecast for Canada calls for a contraction of 6.2% in 2020 (very similar to the BoC's optimistic scenario) followed by a 4.2% rebound in 2021 (very similar to the private sector bank forecasts). The BoC's Pessimistic projection is horrendous, calling for a 19% contraction in 2020, followed by a 4% rebound in 2021.

Another way to view the Bank's projections is to convert them into projections of the output gap, i.e. the gap between projected GDP and potential GDP, which was assumed to be growing at about 1.7% before Covid19. The chart looks similar, but the scale shows that while TD Economics and the PBO expected economic activity to fall about 10% below previous estimates of its' potential, the BoC expects real GDP to fall, optimistically, 15% or, pessimistically, 30% below potential before beginning a quick or slow recovery. In the Optimistic projection, real GDP recovers to near full capacity by the end of 2021. In the Pessimistic projection, real GDP would still be almost 15% below its pre-Covid19 potential at the end of 2021, an outcome which would surely be called a depression.

No wonder the Bank of Canada decided not to publish numerical projections! Doing so would probably have been a shock to the already battered confidence of Canadian businesses and consumers. It would also have implied a much larger budget deficit than that projected by the Parliamentary Budget Office.

Worldwide confirmed cases of Covid-19 ramped up dramatically in March. As the case count grew, governments around the world imposed draconian, but necessary, public health restrictions which have had the effect of shutting down large swaths of the global economy. This has caused a scramble by economists to revise their forecasts from what was a benignly boring view at the beginning of the year that nothing particularly interesting would happen to the economy in 2020.

In February, when Covid-19 was mainly a Chinese phenomenon, that led to the lockdown of Wuhan and Hebei Province, most economists forecast that the virus would have little impact on global growth and that China's economy would slump in 1Q19 but snap back in V-shaped recovery in 2Q19. However, as the virus spread exponentially across the globe in March, economists began to take it seriously and to take down their growth forecasts and consider the possibilities of U-shaped or even L-shaped recoveries. By mid-month, some economists declared a global recession. By month-end, a debate was developing about whether it would be a Recession or a Depression.

For their part, Canadian economists began adjusting their forecasts in early March and progressively downgraded the growth outlook as the month wore on. The chart below shows how forecasts for Canada's real GDP have changed since late February.

The Chart shows real GDP in level terms; it was C$2.1 trillion seasonally adjusted at annual rates in 4Q19. On February 21, the economists at my old employer, JP Morgan, had a close-to-consensus forecast that the economy would grow steadily, if not robustly, at about its' potential rate of 1.7%. By March 13, JPM had downgraded the forecast to show a moderate recession, with growth contracting at annual rates (ar) of -1.5% in 1Q20 and -2.5 in 2Q20, followed by a rebound in growth to about a 3%ar in the second half of the year.

Two weeks later, on March 27, JPM had reassessed the damage and forecast contractions of -5.5%ar and -18.5%ar in the first two quarters of the year, followed by growth averaging 9%ar in the second half. For comparison, Bank of Montreal (BMO) Economics on March 27 forecast contractions of -6.5% and -25%ar in 1Q and 2Q20, followed by a rebound at a stunning 30%ar in 3Q20 and 4% in 4Q. TD Economics made a similar forecast on March 25, but didn't expect as fast a rebound in growth as BMO.

The convention of stating growth at annual rates confuses people by exaggerating the weakening of the economy. The reality, for those who are not growth afficionados, is that BMO, for example, is forecasting that seasonally-adjusted real GDP will contract by -1.7% in 1Q20 and by -7% in 2Q, followed by a 6.8% rebound in 3Q20 and 1% growth in 4Q20. This results in a full year contraction of real GDP of -3% in 2020. Forecasts for 2021 growth now stand at 2.7% for JPM, 3.5% for BMO and 3.7% for TD. It would be helpful and constructive for economists to stop reporting their quarterly forecasts at seasonally adjusted annual rates and just report the actual contraction of real GDP.

This is not to minimize the hit to the economy, it is just to clarify what these economists are telling us. In fact, their arithmetic points to a very sudden and serious recession. The range of forecasts is fairly large, even though all of the forecasters expect the economy to be recovering by 3Q20. All of the forecasters are assuming that Covid19 cases will peak in 2Q and subside in a manner similar to that experienced in China or South Korea. If new cases take longer to peak or if there is a resurgence of new infections in the autumn, the rebound in real GDP will be slower and take longer than in the current forecasts.

Even if the current forecasts are close to accurate, they point to a significant loss of real output and incomes. The output gap is forecast to widen to the 7-9% of GDP range in 2Q20. Real incomes will likely fall by even more as Canada's terms of trade have fallen sharply due to the drop in crude oil and other commodity prices. Even in the most optimistic forecast, real GDP will not return to its' potential by the end of 2021. BMO forecasts that even six quarters into the recovery, the output gap would still be almost 3% of GDP, while JPM and TD see the gap still at almost 4% of GDP. Forecasters seem to be suggesting that there Covid19 is causing a permanent loss of output and income and a downshift in the future path of the level of real GDP.

While economists have spent considerable effort attempting to estimate the immediate hit to real GDP, they seem to have spent less time thinking about the impact of Covid19 on inflation. The chart below shows some of the latest inflation forecasts.

Before significant adjustments in forecasts were made, as illustrated by JP Morgan's February 21 forecast, the outlook was for CPI inflation to remain well behaved and to converge to the Bank of Canada's 2% target by the end of 2020 and to remain there through 2021. By March 27, all forecasters had built in a dip in inflation in 2Q20 followed by a steady return to the 2% target or slightly higher by the end of 2021. BMO projects the biggest dip in inflation to just 0.3% over a year ago in 2Q20, and despite their forecast of a sharp snapback in real GDP in 3Q20, still expects inflation to be just over 1%oya in 1Q21. Perhaps because they have been well trained by the Bank of Canada's projections, all forecasters expect inflation to converge to close to target within two years. Yet, as mentioned above, these forecasters still expect an output gap (excess capacity) of between 3 and 4% of GDP by the end of 2021.

Some forecasters may rationalize this return to target inflation despite a still sizable output gap by assuming that potential GDP estimates will be permanently reduced by the Covid19 crisis. It is not clear why this should be the case. The growth of the labour force is not likely to be affected unless the government indefinitely closes the border to immigration. And there is no reason to mark down potential estimates of productivity unless economists believe that Covid19 will a permanent depressing effect on capital investment. These outcomes are possible, but only likely if the economic shutdown lasts much longer than is assumed in current forecasts.

Bank of Canada Governor Poloz noted the lowered growth and inflation forecasts as the Bank cut its policy rate to the "effective lower bound" of 0.25% from 1.75% at the end of February. Poloz said that the lowered forecasts he was seeing were little more than arithmetic and promised to unveil new projections on April 15th from the Bank of Canada's forecasting team, which he described as "the best there is". He suggested that more than just doing arithmetic, the Bank of Canada's forecasters would take account of confidence effects and how behavior might change in the post-Covid19 world. One suspects that the Bank will provide a range of scenarios based on differing assumptions about the course of the Covid19 pandemic and the likely economic repercussions of a shorter or longer crisis.

Many questions are not answered, or even addressed, in these forecast revisions. Will government support programs and a huge increase in deficit spending prevent corporate defaults and a permanent destruction of economic capacity. If debt defaults are too large, will that tigger persistent higher unemployment and unleash deflationary forces? Will Canada's highly productive energy industry be able to recover when government policies are tilted toward "phasing out" fossil fuels? Will financial markets take in stride the coming huge spike in Canada's federal debt-to-GDP ratio, or will investors demand a higher credit risk premium for a country which already has very high levels of household and corporate debt? Will the Bank of Canada's policy interest rate setting stay at the effective lower bound indefinitely, and if so, will bond markets anticipate higher inflation and bond yields? Perhaps the Bank of Canada's crack forecasting team will shed some light on these questions. But probably not.

The rapid global spread of the Covid-19 virus and the precautionary health measures being taken in many countries to stem the pandemic have created turmoil in financial markets. Most global stock markets are in correction -- down more than 10% from their recent highs. Global bond yields have plunged -- the 10-year US Treasury yield touched a record low of 1.12% on February 28, before closing at 1.16%. The 10-year Canada bond closed at 1.13%, down from a recent high of 1.70% on November 2 and the lower than in January 2015 when the Bank of Canada last cut the policy rate. Commodity prices have plunged as global demand has cratered. The benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil price has dropped 27.5% to $45.26 from $62.43, its recent high in early January. Western Canadian Select (WCS), Canada's benchmark crude price has fallen to $31.69 from a high of $58 in May 2018. The turmoil in asset markets is a reflection of repricing in highly liquid financial markets reflecting investor's expectations, based on current information, of how activity levels are being affected by containment efforts to halt the global spread of coronavirus.

The spread of Covid-19 is creating a chain reaction of economic effects. The initial outbreak in China, which probably began in December but was not acknowledged until late January, led to public health measures which caused workers to stay away from work, travelers to stop traveling, and consumers to stay away from shops, restaurants and entertainment venues. Coal consumption fell 40% as factories were shut down. Supply chains that depend upon Chinese manufactured goods were interrupted. Shipping volumes dropped sharply.

Economists have been scrambling to monitor the contraction in economic activity. In the early days, many economists suggested the the impact would be minor, merely causing a slowdown in China's economic growth in 1Q19 that would be fully made up in a V-shaped bounce back in 2Q19. However, as February wore on, it became abundantly clear that the virus had not been contained. Outbreaks in other countries including Japan and South Korea, on passenger ships, and eventually further afield in Iran and Italy made it clear that Covid-19 had become a pandemic, even if the World Health Organization was reluctant to say so. Now, economic activity has stalled in Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo, Seoul and Milan. Countries around the world are warning their citizens to prepare for Covid-19 outbreaks. In Canada, the federal health minister has suggested that citizens put together survival kits to see them through the possibility of two weeks or more of self-imposed quarantine.

As time has passed, economists have progressively cut their forecasts for 2020 economic growth and in many cases have acknowledged that a V-shaped rebound in 2Q19 is becoming much less likely as the virus continues to spread internationally.

The Bank of Canada's Dilemma

In January, Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz revealed that the Bank's forecast for growth of Canada's real GDP in 4Q19 had been cut to 0.3% at an annual rate from the October forecast of 1.7%. The Bank projected a modest rebound in 1Q20 growth to 1.3% and to about 2% in subsequent quarters of 2020. In releasing these projections along with a decision to leave the policy rate unchanged at 1.75%, Governor Poloz said,

All things considered, then, it was Governing Council’s view that the balance of risks does not warrant lower interest rates at this time. In forming this view, we weighed the risk that inflation could fall short of target against the risk that a lower interest rate path would lead to higher financial vulnerabilities, which could make it even more difficult to attain the inflation target further down the road. Clearly, this balance can change over time as the data evolve. In this regard, Governing Council will be watching closely to see if the recent slowdown in growth is more persistent than forecast. In assessing incoming data, the Bank will be paying particular attention to developments in consumer spending, the housing market and business investment.

Since making this statement, real GDP growth in 4Q19 did match the BoC's anemic projection of 0.3% at an annual rate. Early data for 1Q20 has been mixed with housing starts, real exports and total employment modestly firmer in January but with total hours worked, the manufacturing PMI and real imports all down from the 4Q19 average. Activity levels in February will have been depressed by the rail and port blockades by activists protesting the Coastal Gas Link Pipeline.

Global growth forecasts for 1Q20 have been progressively marked down over the past few weeks as the spread of Covid-19 moved quickly and became an incipient pandemic that was likely to last longer and deal a bigger blow to global activity than originally thought.

If the Bank of Canada was worried in mid-January, before the Covid-19 pandemic began, that the late-2019 slowdown in growth might be more persistent, there can be no doubt that the downside risks to both growth and inflation have increased substantially since then.

Why the BoC should be easing

Even before the spread of Covid-19 and the precautionary actions that are slowing global commerce, there was strong reason for the Bank of Canada to follow the lead of the US Fed and numerous other central banks since mid-2019 in cutting their policy rates.

Since early May 2018, Canada's commodity prices have been falling. When commodity prices fall, Canada's terms of trade weaken as the prices of our exports fall relative to the price of our imports. Historically, the Bank of Canada has responded to sharp falls in commodity prices and the terms of trade by easing monetary conditions through a combination of lowering the policy rate and allowing the Canadian dollar to weaken against foreign currencies. The Bank last did this in early 2015 when crude oil prices collapsed.

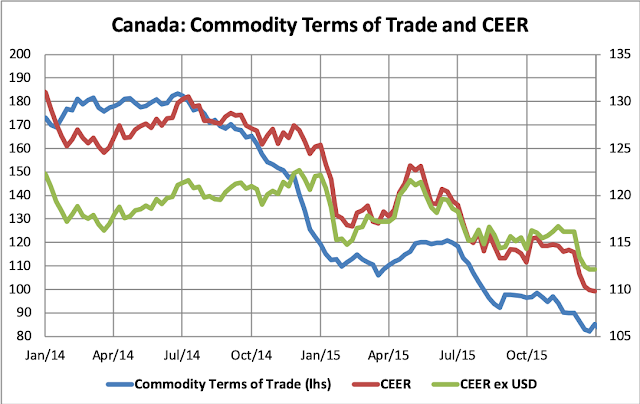

In the chart below, for the 2014-15 period, the commodity terms of trade, which I define as the Bank of Canada's commodity price index divided by the core CPI, is shown alongside the BoC's measure of Canada's nominal effective exchange rate (CEER). The CEER is shown against all currencies and also against all currencies excluding the US dollar.

As the chart clearly shows, the commodity terms of trade dropped sharply in late 2014 as world and Canadian crude oil prices collapsed. As this occurred, Canada's effective exchange rate weakened because of a weakening of the Canadian dollar versus the US dollar, while excluding the USD, the effective exchange rate actually strengthened until January 2015. In January, the Bank of Canada stunned market participants by cutting the policy rate, which triggered a sharp fall in the effective exchange rate, both including and excluding the USD. The weakening of the CAD helped cushion the blow of the oil price collapse on oil-producing regions of Canada and helped improve the export competitiveness of other sectors and regions of the economy.

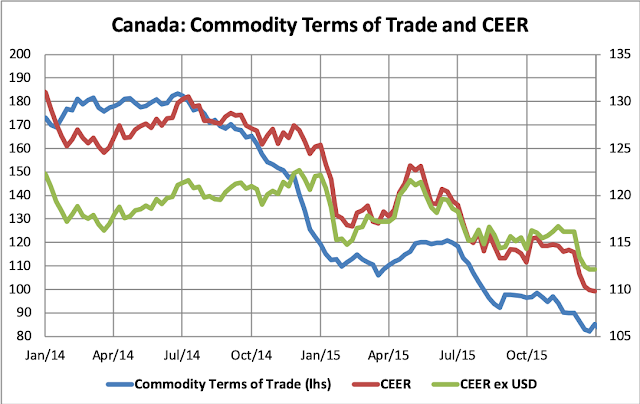

Now look at the same chart for the 2018-20 period.

Once again, the commodity terms of trade peaked in May 2018 before falling sharply in late 2018 as central bank tightening, led by the US Fed, raised recession fears. Slowing growth and the sharp fall in commodity prices, along with a melt-down of global equity markets, caused the Fed and other major central banks to reverse course by cutting their policy rates and, in some cases, adding liquidity by expanding their balance sheets through quantitative easing. The Bank of Canada was an outlier, choosing not to follow suit with rate cuts of its own. The result was that, despite a sharp weakening in commodity prices, Canada's nominal effective exchange rate appreciated. This not only made times more difficult for commodity producing sectors and regions, but also caused a deterioration in the export competitiveness of Canada's manufacturing exports at a time of stagnating global trade. The Bank of Canada, through this period, expressed concern about the risk that high household debt levels posed to financial stability. The BoC made a clear trade-off, attempting to constrain household borrowing, especially mortgage borrowing in Toronto and Vancouver, at the expense of Canada's commodity sector and other export oriented industries.

Since the onset of Covid-19, commodity prices have renewed their decline. The commodity terms of trade have now weakened 27.5% since May 2018, half of the steep decline in 2014-15. The 2014-15, the 52% decline in the commodity terms of trade was cushioned by a depreciation of 22% against the USD, a depreciation of the nominal effective exchange rate of 15%, and an effective depreciation of 7.5% against non-US trading partners. The 27.5% decline of the commodity terms of trade since May 2018 has been accompanied by just a 1.6% depreciation against USD, but a 1.6% appreciation in the nominal effective exchange rate, providing no relief for commodity producers and a deterioration in the competitiveness of other exporters. Alberta, Saskatchewan, Northern BC and Newfoundland are suffering not only from weak commodity prices and regulatory strangulation, but also from a strong exchange rate generated by the BoC's unwillingness to cut the policy rate. Auto plants in Ontario are closing or laying off workers as Canada's competitiveness weakens.

We are just now beginning to see the economic impact of Covid-19. Purchasing managers' surveys showed activity levels collapsed in both the manufacturing and services sectors in China. Declines are also likely to be recorded in Japan, Korea and other Asian countries in February. Measures now being taken in Europe and the United States suggest that as the virus spreads, so too will the economic weakness.

Here in Canada, where hard economic data is published with a lag of up to six weeks relative to the United States, it would be foolish to wait for statistical evidence for the BoC to take action and cut the policy rate. Even without Covid-19, the failure to cut policy rates along with other major central banks has slowed growth and done so at the expense of the weakest sectors and regions of the country.