As the year comes to a close, it is time to review how the macro consensus forecasts for 2017 that were made a year ago fared. Each December, I compile consensus economic and financial market forecasts for the year ahead. When the year comes to a close, I take a look back at the forecasts and compare them with what we now know actually occurred. I do this because markets generally do a good job of pricing in consensus views, but then move -- sometimes dramatically -- when a different outcome transpires. When we look back, with 20/20 hindsight, we can see what the surprises were and interpret the market movements the surprises generated. It's not only interesting to look back at the notable global macro misses and the biggest forecast errors of the past year, it also helps us to understand 2017 investment returns and to assess whether they are sustainable.

Real GDP

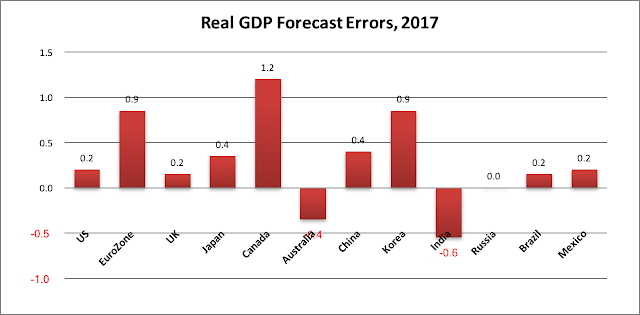

In 2017, for the first time in years, forecasters underestimated global real GDP growth. Average real GDP growth for the twelve countries we monitor is now expected to be 3.6% compared with a consensus forecast of 3.3%. In the twelve economies, real GDP growth exceeded forecasters' expectations in nine and fell short of expectations in just two. The weighted mean absolute forecast error for 2016 was 0.43 percentage points, down slightly from the 2016 error.

Based on current estimates, 2017 real GDP growth for the US exceeded the December 2016 consensus by 0.2 percentage points compared with a 0.8 downside miss in 2016. The biggest upside misses for 2017 were for Canada (+1.2 pct pts), Eurozone (+0.9), Korea (+0.9), China (+0.4) and Japan (+0.4). India's real GDP undershot forecasts by 0.6 pct pts and Australia by 0.4. On balance, it was the first year in seven that global growth exceeded consensus expectations.

CPI Inflation

Inflation forecasts for 2017 were, once again, too high. Average inflation for the twelve countries is now expected to be 2.2% compared with a consensus forecast of 2.5%. Eight of the twelve economies are on track for lower inflation than forecast, while inflation was higher than expected in three countries. The weighted mean absolute forecast error for 2016 for the 12 countries was 0.58 percentage points, a much larger average miss than last year.

The biggest downside misses on inflation were in Russia (-2.4 pct pts), Brazil (-1.1), China (-0.7), and Canada (-0.6). The biggest upside miss on inflation was in Mexico (+2.7 pct pts).

Central Bank Policy Rates

In 2017, for the first time in many years, economists' forecasts of central bank policy rates were too low.

In the DM, the Fed hiked the Fed Funds rate three times, more than the consensus expected. The ECB had been expected to keep its Refi rate unchanged, but surprised forecasters by lowering it to -0.4%. The Bank of Canada and the Bank of England had been expected to leave rates unchanged in 2017, but the BoC unexpectedly hiked twice and the BoE hiked once. In Australia, the consensus leaned toward a rate cut in 2017, but the RBA stayed on hold. The Bank of Japan met expectations and stayed on hold at -0.1%. In the EM, the picture was more mixed. Brazil's central bank was able to cut its policy rate much more than expected as inflation eased, while Russia was also able to cut its policy rate a bit more than expected. In China, the PBoC stayed on hold, as expected, while India's RBI eased 25bps, also in line with expectations. Mexico extended the trend of late 2016, tightening 100 bps more than expected as inflation rose sharply in delayed response to the weakening of the Mexican Peso as NAFTA came under heavy fire from the Trump Administration.

10-year Bond Yields

In six of the twelve economies, 10-year bond yield forecasts made one year ago were too high. Weaker than expected inflation combined with aggressive bond buying by the the ECB pulled 10-year yields down in most DM countries compared with forecasts of rising yields made a year ago.

In four of the six DM economies that we track, 10-year bond yields surprised strategists to the downside. The weighted average DM forecast error was -0.30 percentage points. The biggest misses were in the UK (-0.48 pct. pt.), US (-0.35), Eurozone (proxied by Germany, -0.34) and Australia (-0.30). In the EM, the picture was mixed as bond yields were lower than forecast where inflation fell more than expected, in Brazil (-2.05 pct pts) and Russia (-1.54). Bond yields were higher than expected in China, India and Mexico.

Exchange Rates

All of the major currencies (with the exception if the UK sterling) were stronger than expected against the US dollar. The weighted mean absolute forecast error for the 11 currencies versus the USD was 7.7% versus the forecast made a year ago, a larger error than last year.

The USD was expected to strengthen following the election of Donald Trump as President. Trump's criticism of the Fed during the 2016 election (implying that Fed Chair Janet Yellen would not be reappointed) and his plans for deregulation and fiscal stimulus had most forecasters expecting the USD to hold steady or strengthen against most currencies. As it turned out, delays in implementation of Trump's promises, hesitation by the Fed, unexpected tightening by some other central banks and ebbing political uncertainties in emerging countries saw the USD weaken against all currencies with the exception of Sterling, which struggled under the weight of Brexit uncertainty.

The biggest FX forecast misses were for the Euro (which was 10.8% stronger than expected), Russian Ruble (+10.1%) and Korean Won (+11.0%). The Canadian Dollar (+7.7%) and the Mexican Peso (+6.4%) were stronger than expected, despite NAFTA worries, as the central banks of both countries tightened more than forecasters had expected. China, India and Brazil also saw greater than expected currency strength.

Equity Markets

A year ago, equity strategists were optimistic that North American stock markets would turn in a modest, unspectacular positive performance in 2017. News outlets gather forecasts from high profile US strategists and Canadian bank-owned dealers. As shown below, those forecasts called for 2017 gains of 6.0% for the S&P500 and 4.3% for the S&PTSX Composite.

However, global real GDP growth surprised on the upside and global inflation surpassed on the downside, both misses being positive for equities. As of December 26, 2017, the S&P500, was up 19.9% year-to-date (not including dividends) for an error of +13.9 percentage points. The S&PTSX300 was up a more modest 5.8% for an error of +1.5 percentage points.

Globally, stock market performance (in local currency terms) was impressive. Japan and most emerging markets (with the exception of Russia) posted the best gains. Canada and Mexico were laggards.

Investment Implications

In 2017 global macro forecast misses were quite different from those of recent years. Real GDP growth exceeded expectations for the first time in seven years. CPI inflation continued to surprise on the downside, but several major central banks tightened more than expected despite weak inflation. However, the impact of higher than expected policy rates on bond yields was more than offset by the ECB's move to a significantly negative policy rate combined with continued large scale bond purchases. Consequently, even though major central banks tightened more than expected, bond yields came in lower than expected. And even though the US Fed led the move to tighten, the USD was weaker than expected against all of the major currencies expect UK Sterling.

Stronger than expected global growth, lower than expected inflation, and a smaller than expected rise in bond yields boosted equity performance in virtually all markets. US equities posted double-digit returns for a second consecutive year. The combination of better than expected real GDP growth and stimulative monetary policy boosted Japanese stocks and European stocks. Strong global growth and reduced political uncertainties facing Brazil and Russia helped lift Emerging Market equities to robust gains. In China, equity prices rebounded as Trump's protectionist campaign rhetoric against China was moderated by the US need for Chinese cooperation against North Korea's nuclear threat. Instead, Trump's protectionism was focussed on renegotiating NAFTA with Canada and Mexico, whose stock markets underperformed.

For Canadian investors, the stronger than expected appreciation of CAD against the USD meant that returns on investments in both equities and government bonds denominated in US dollars were reduced if the USD currency exposure was left unhedged. The biggest winners for unhedged Canadian investors were Eurozone, Japanese and Emerging Market equities.

The outperformance globally diversified portfolios over stay-at-home Canadian portfolios reasserted itself in 2017. As 2018 economic and financial market forecasts are rolled out, it is worth reflecting that such forecasts form a very uncertain basis for year-ahead investment strategies. While forecasters' optimism about global growth appears high, 2018 will undoubtedly once again see some large consensus forecast misses, as new surprises arise. The 2017 surprises, higher than expected growth and lower than expected inflation are now being built in to 2018 views. This actually increases the chances of disappointments that are negative for equities and other risk assets. With unconventional monetary stimulus being questioned and central banks belatedly beginning to focus on containing debt growth rather than hitting inflation targets, the scope for unfriendly surprises is rising.

In the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), it was widely acknowledged that traditional macroeconomic models of aggregate demand and aggregate supply had failed to provide early warning signals of the financial collapse that was to come.

While most economists focus on the business cycle, identified by peaks and troughs in real GDP, they have had remarkably limited success in forecasting when recessions will occur. Following the GFC, some analysts have shifted their attention toward the financial side of the economy and longer-term credit cycles.

Ray Dalio of Bridgewater Associates has become famous, not only for building the world's biggest hedge fund, but also for his analysis of How the Economic Engine Works, which is founded on the concepts of the short-term debt cycle (equivalent in Dalio's view to the business cycle) and the long-term debt cycle (equivalent to booms and busts in financial markets which trigger bubbles and busts in asset markets).

John Geanakopolos of Yale University has identified what he calls the leverage cycle. As the Wall Street Journal reported:

Geanakopolos theorized that when banks set margins very low, lending more against a given amount of collateral, they have a powerful effect on a specific group of investors.... Using large amounts of borrowed money, or leverage, these buyers push up prices to extreme levels. Because those prices are far above what would make sense for investors using less borrowed money, they violate the idea of efficient markets. But if a jolt of bad news makes lenders uncertain about the immediate future, they raise margins, forcing the leveraged optimists to sell. That triggers a downward spiral as falling prices and rising margins reinforce one another. Banks can stifle the economy as they become wary of lending under any circumstances.

Claudio Borio, Head of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Monetary and Economic Department, analyses what he refers to as the financial cycle. As The Economist magazine quoted Borio:

In the environment that has prevailed for at least three decades now, just as in the one that prevailed in the pre-WW2 years, it is simply not possible to understand business fluctuations and their policy challenges without understanding the financial cycle. This calls for a rethink of modelling strategies. And it calls for significant adjustments to macroeconomic policies.

According to Borio, the financial cycle can be understood as a sequence of "self-reinforcing interactions between perceptions of value and risk which translate into booms followed by busts". The financial cycle has several salient features that often cause it to be ignored by mainstream economists. First, it has a much lower frequency than a typical business cycle. Instead of going from peak to trough every 5-7 years, the financial cycle can take decades. Patterns of economic activity on both the upside and downside simply do not make sense unless the high-frequency business cycle is overlaid on top of the slower-moving financial cycle. Second, the amplitude of the financial cycle is very wide compared to the amplitude of the normal business cycle. This combination means that the financial cycle produces sustained booms and deep downturns.

While Dalio's debt cycle, Geanakopolos' leverage cycle, and Borio's financial cycle use different names, all three are highlighting cycles, not in aggregate spending or GDP, but in debt, leverage or credit growth that create self-reinforcing accelerations or decelerations in financial and economic activity.

Personally, I prefer the term credit cycle which harkens back to Hyman Minsky's theory of financial instability and the view that the credit cycle is the fundamental process driving the business cycle.

While much has been written about the credit cycle in global financial circles, there has been unfortunately little acknowledgement or application of this recent strand of research to Canadian economic forecasting or policy-making. This relative lack of attention is more striking because, since the GFC, Canada has experienced a credit boom of epic proportions.

Canada's Credit Cycle

For over a decade, analysts at the BIS and elsewhere have compiled methodologically consistent historical credit data for a wide range of advanced and emerging economies. In recent reports, the BIS have employed its measure of the credit-to-GDP gap (or Credit Gap) to identify countries a that are subject to heightened risk of financial crisis. The Credit Gap is defined as the difference between the credit-to-GDP ratio and its long-term trend. The two charts below show the credit-to-GDP ratio and the Credit Gap for Canada with the same measures for the United States shown for comparison.

In both countries, the credit-to-GDP ratios have risen steadily over the decades. In both countries, the ratio rose from about 75% of GDP in the late 1950s to about 170% by 2007, at the onset of the GFC. Since then, the ratios have diverged sharply, with Canada continuing to increase leverage to a peak of 219% of GDP in 3Q:16, while the US deleveraged to a ratio just over 150% over the same period. The chart clearly shows that after tracking each other quite closely from the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s, leverage cycles in the two countries have become much less closely linked.

The second chart shows the BIS measure of the Credit Gap in the two countries. Since the mid-1970s, while the US has experienced two very pronounced peaks and troughs in its credit gap, Canada has experienced four pronounced peaks and three troughs.

The peaks in the US credit gap occurred in 1987 and 2007. The first peak coincided with the 1987 stock market crash and was an early warning signal of the bursting of the real estate bubble and the S&L Crisis of the early-1990s. The second peak coincided with the peak of the US housing boom and was an early warning signal of the Great Financial Crisis that saw the failures of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers.

The peaks in Canada's credit gap occurred in 1979, 1991, 2009 and 2016. It is noteworthy that Canada's latest three credit gaps all exceeded the peak levels seen in the US in 1987 and 2007. The peak in 1979 was a precursor to the deep 1981-82 recession. The peak in 1991 followed shortly after a peak in housing prices amid the 1990-91 recession. The peak in 2009, as in 1991, came amid another recession in 2008-09. The apparent peak in 2016, the biggest credit gap ever recorded for Canada, looks to be a precursor to another peak in housing prices which is unfolding as we watch in 2017.

Canada's Credit Gap and Real GDP Growth Gap

Whether the 2016 peak in Canada's credit gap is an early warning signal of another recession remains to be seen. But an inspection of how cycles in credit growth line up with cycles in real GDP growth suggests a serious risk that the Canadian economy is on the cusp of at least a sharp slowdown in real GDP growth.

The chart below compares Canada's credit gap with its real GDP growth gap. The real GDP growth gap, analogously to the credit gap, can be defined as defined as the difference between real GDP growth and its long-term trend.

While this chart doesn't appear to show a close relationship, my calculation is that the levels of peaks and troughs in the credit gap have a 90% correlation with the level of peaks and troughs in the real GDP growth gap. This may sound complicated, but its not. Using all of the peaks and troughs in the credit gap and the real GDP growth gap, it implies that higher credit gap peak levels have been associated with higher real GDP growth gap peaks and lower credit gap trough levels have been associated with lower real GDP growth gap trough levels.

Conclusion

We apparently have seen a peak in Canada's credit gap in 3Q16 at its highest level ever. We have apparently subsequently seen a peak in the real GDP growth gap in 2Q17, as growth in 3Q17 seems to be slowing sharply. Many commentators have been crowing about Canada's recent growth spurt, but the history of cycles in Canada's credit gap suggests that, far from signalling a sustained acceleration of real GDP growth, the peak in the credit cycle is probably signalling the beginning of what could become a serious growth slowdown in real GDP growth ... or worse.

The Great Unwind of extraordinarily accommodative global monetary policy got underway in earnest in June, 2017. Until then, though the Fed had begun reducing monetary ease at the end of 2015, other major central banks had maintained very easy policies.

Then, as if on cue, the European Central Bank expressed confidence in the strength of Euro Area growth and mused about reducing its bond purchases (June 8); the Bank of Canada's top officials suddenly executed a U-turn from ruminations about cutting rates in January to contemplating early rate hikes (June 12-13); the Federal Reserve hiked its policy rate and discussed reducing its' $4.5 trillion balance sheet (June 14); and Bank of England Governor Mark Carney said the BoE may need to begin raising interest rates and would debate a move in the next few months (June 28).

Increasing the likelihood that these central bank unwinding moves were coordinated was the Bank for International Settlements Annual Report, released on June 25, titled Monetary Policy: Inching Toward Normalization, which laid out the case for removing monetary stimulus even though inflation remains well below target in virtually all of the major advanced economies.

The coordinated central bank (CB) unwinding of monetary stimulus has been widely applauded as a recognition that global growth has strengthened, global slack has diminished and global debt-to-GDP ratios had risen to all-time highs, posing financial stability risks. But despite the fact that unprecedented global monetary policy accommodation had fuelled asset price growth for years, few commentators raised concerns that unwinding monetary policy stimulus might have negative consequences for global asset prices.

This post takes a brief look at how the Great Unwind has affected Canadian investors. I do this through the lens of the global ETF portfolios for Canadian investors that I regularly track in this blog.

The chart below shows year-to-date total returns for these portfolios, in Canadian dollar (CAD) terms.

The chart shows returns for five portfolios: an all-Canadian ETF portfolio (Cdn 60/40) made up of 60% Canadian equities (XIU), 35% Canadian bonds (XBB) and 5% Canadian real return bonds (XRB); a Global 60/40 portfolio including both Canadian and global equity and bond ETFs; a more conservative Global 45/25/30 portfolio made up of 45% global equity ETFs, 25% global bond ETFs and 30% cash, a Global Levered Risk Balanced Portfolio (Gl Lev RB), which uses leverage to balance the expected risk contribution from the Global Market ETFs, and a Global Unlevered Risk Balanced Portfolio (Gl UnL RB), which has less exposure to government bond ETFs, inflation-linked bond ETFs and commodity ETFs than the levered risk balanced portfolio but more exposure to corporate credit ETFs.

As is evident from the chart, all of these portfolios performed well into early June, peaking in the week ending June 2. After the ECB signalled its change of direction on June 8, all of the portfolios began to give back their gains. The Global 60/40 portfolio, which had the strongest year-to-date (ytd) gain of 8.2% on June 2, has given back about two-thirds of its gain and was up just 2.9% for the year by the week ended July 28. Hardest hit was the Global Risk Balanced Portfolio, which went from a ytd gain of 8.1% on June 2 to a ytd loss of 1.8% by July 28. The gain in the all-Canadian portfolio, which had struggled to a 2.9% ytd return by June 2, had been erased to a 0.1% loss by July 28.

If the global and Canadian economies are faring so much better, why have investment returns for Canadian investors turned so negative in the Great Unwind? The answer is that the swift turnaround in the stance of the BoC caught markets by surprise and caused the Canadian dollar to surge against the US dollar and other currencies. The surge in CAD has imposed losses on unhedged investors in global ETFs denominated in US dollars. As shown in the chart below, every ETF tracked in this blog has experienced negative returns in CAD terms since the CB Unwind began in early June.

The more hawkish BoC stance has also seen Canadian interest rates back up, pushing Canadian bond prices down and causing losses on Canadian bond ETFs. Making matters worse, the Canadian equity ETF (XIU) has been one of the worst performers (in local currency terms) among global equity ETFs since the Great Unwind began, losing 2.4%. While US, Eurozone, Japanese, and Emerging Market ETFs have had better local currency returns, the surge in CAD has meant that these ETFs have experienced even bigger losses than XIU in Canadian dollar terms.

Losses on global bond ETFs range from -4.5% to -9.0% in CAD terms since early June. Losses on global, equity ETFs range from -3.3% to -6.4%. Losses on gold and commodity ETFs range from -6.3% to -8.1%. The result is that returns for Canadian investors on globally diversified portfolios have been hammered since the Great Unwind began, reducing or totally erasing the promising gains of the first five months of 2017 as shown in the chart below.

There is a slight silver lining to the Great Unwind black cloud for Canadian investors. The chart below compares the Great unwind losses for currency unhedged portfolios with those portfolios that were USD-hegded. If foreign ETF holdings were USD-hedged, the globally diversified portfolios would have experienced small gains since June 2, much better performance than the all-Canadian portfolio.

Unfortunately, most Canadian investors do not fully hedge their foreign currency exposures. Indeed, some large pension funds and the majority of individual investors do not hedge at all. My guess would be that far less than half of Canadians' holdings of C$1.8 trillion of foreign portfolio investments (of which $1.1 trillion are USD-denominated) are currency hedged. Based on this assumption, and on the holdings of Canadian bonds and equities, my back of the envelope estimate of the losses to Canadian investors since the beginning of the Great Unwind in early June would be in the neighbourhood of C$150 billion.

The Bank of Canada is an inflation-targeting central bank. It sets monetary policy with an objective of returning the inflation rate to the 2% target within six to eight quarters. Because this is the objective, the Governing Council of the BoC always projects that six to eight quarters from the current period, inflation will be 2%. If it did not do so, it would be admitting either that it cannot achieve the 2% target or that for some special reason it would not be appropriate to attempt to achieve the target. To my recollection, the latter has never happened.

Four times a year, the BoC publishes the Monetary Policy Report, in which the Governing Council reveals its projection for inflation over the coming two years. The inflation projection is important because it shapes expectations about the likely future path of the Bank of Canada's policy rate. For example, if the current inflation rate is below the 2% target (as it is currently), but the BoC projects that inflation will return to the 2% target over the next six or twelve months, then there would tend to be an expectation that the BoC would reduce the amount of monetary stimulus over that period.

One would expect that the BoC would be expert at projecting inflation. After all, the BoC undoubtedly has the largest number of highly educated economists of any institution in Canada and they are focussed on projecting inflation. The BoC has access to whatever resources are required, including model building capability, as well as input from top academic and private sector advisors. And most importantly, the BoC controls the monetary policy tools that can influence the inflation rate. So it seems reasonable to ask the question: With all of these resources, with a strong government mandate, and with independent control of the policy levers: Can the Bank of Canada accurately project future inflation?

Reviewing the Track Record

To answer the question, we must look at the projections of inflation that the BoC has made. In this post, I review the track record of the current decade, starting in January 2010. This is the period following the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) during which Mark Carney and Stephen Poloz have been the BoC Governors.

To conduct the review, I have compiled the projections of inflation made in each Monetary Policy Report since January 2010 and compared the projections with inflation outcomes one year later. I have reviewed the projection accuracy for both Total CPI inflation and Core CPI inflation. Shown below is the actual performance of total and core inflation, shown as quarterly averages since the beginning of 2010.

Over this period, total inflation has averaged 1.66% and core inflation has averaged 1.73%. Total inflation was below the 2% target 70% of the time (21 out of 30 quarters) and core inflation was below the target level 60% of the time.

Now let's look at how accurately the BoC Governing Council projected total and core inflation one year ahead. The charts below show the actual outcomes against the BoC Projections made one year earlier.

The chart for total inflation shows that the BoC consistently projected that inflation would return to close to 2%, while the actual outcomes varied significantly, between 0.7% and 3.4%. By my calculation, the average absolute error of the BoC's 1-year forward projections for total inflation has been 0.63 percentage points (ppts) which amounts to 38% of the average inflation rate over the projection period and 90% of the standard deviation of total inflation over the period.

The chart for core inflation shows less variability in both actual outcomes and the BoC's projections. Since the January 2010 MPR, the one-year forward core inflation projection has never varied outside the range of 1.8% to 2.1%. Actual outcomes for core inflation have varied between 1.2% and 2.2%. The average absolute error of the BoC's 1-year forward projections for core inflation has been 0.37 ppts, which amounts to 21% of average core inflation rate and 100% of the standard deviation of core inflation over the projection period.

I conducted another test to compare the accuracy of the BoC's projections with those of a naive forecasting approach. The naive approach was to assume that total CPI inflation would revert to its rolling 10-year average over the 1-year projection period. The 10-year average of the total inflation rate has been falling consistently, from 2.1% in the second quarter of 2012 to 1.6% in 2Q17. A naive forecast that total inflation in one year's time would be equal to its latest 10-year average would have produced an average absolute error or just 0.28 ppts, less than half of the error of the Bank of Canada's projections.

You can be your own judge of these results, but from my perspective, the BoC's inflation projections since 2010 have shed virtually no light on where inflation was heading. A methodology that results in a projection error equal to 90-100% of the standard deviation of the indicator being projected is not of much value. It is a poor guide to setting monetary policy.

Implications and Conclusions

The Bank of Canada is apparently not the only central bank that can't forecast inflation accurately. Brad DeLong, Professor of Economics at the University of California at Berkeley, recently took the US Fed to task for it's inflation forecasts.

In terms of inflationary pressure, the Fed’s forecast seems to have significantly overstated the strength of the US economy.... The FOMC’s blind spot stems from the fact that it is relying more on its assessment of the labor market, which it considers to be at or above “full employment,” than on noisy month-to-month inflation data. But “full employment” is a rather tenuous and unreliable construct....

The Fed clearly needs to take a deep look at its forecasting methodology and policymaking processes. It should ask if the current system is creating irresistible incentives for Fed technocrats to highball their inflation forecasts. And it should ensure that its policymakers view the 2% target for annual inflation as a goal to aspire to, rather than a ceiling to avoid.

Another, less academic but perhaps more insightful, assessment comes from the excellent Randall Forsyth, Associate Editor of Barrons and author of the weekly "Up and Down Wall Street" column:

There seem to be two parallel universes—one described by theory, the other by reality. Most of us occupy the latter, while the former is the province of academics and policy makers.

In the theoretical world, low unemployment threatens to unleash a torrent of inflation, which needs to be staved off by tighter monetary policies. Back in the real world, disruption, innovation, and competition relentlessly drive down prices while wage growth is hard to come by.

My own conclusion is that the Bank of Canada's projections of inflation are likely to be less accurate than the rolling 10-year average, which currently sits at 1.6%, below the BoC's inflation target. The recent musings of BoC Governor Poloz that signs of improvement in Canadian economic activity might merit the removal of some monetary stimulus represent a highly speculative view based on projections from output gap models that have not performed as well as naive rules. This implies that, for the Governor's view to be justified, either the BoC's forecasting record must suddenly improve or that the BoC must be more concerned about the potential risks to financial stability created by the extraordinarily low policy rate required for sustained pursuit of the BoC's 2% inflation target.

Last year it was Vancouver house prices. This year it is the Toronto housing "crisis" that has politicians panicking. In March, the average Toronto house price was up 33% over a year ago. This news sparked a meeting of "three wise men" -- Canada's Finance Minister Bill Morneau, Ontario's Finance Minister Charles Sousa, and Toronto's Mayor John Tory -- to collaborate on appropriate actions to ease the panic.

The three wise men agreed that they should refrain from adopting policies which would add to already overheated demand. Then within days, Ontario's Liberal government announced a "suite" of measures to respond to what they claimed was a public clamour for government intervention. Premier Kathleen Wynne and Mr. Sousa, not wanting to let a good crisis go to waste, seized the opportunity to impose a new 15% tax on non-resident buyers and tighten housing regulation in the worst possible way by imposing strict rent controls. Unfortunately, such actions that are more likely to worsen rather than improve the fundamental problem of insufficient supply of reasonably priced housing.

I am returning to the issue of housing prices after writing about it in March, 2014 in Why So Paranoid About Canada's Housing Market, and again in June 2016 in China Stimulus and Vancouver House Prices.

In March 2014, I argued that, while some high profile commentators thought Canada was in the midst of a housing bubble that was on the verge of bursting, my research showed that Canada's housing prices were still good value relative to house prices in other countries and that there was no reason to think that a Canadian house price bubble was about to burst. Looking back, that view proved correct. Far from bursting, house prices in Vancouver, in Toronto and in several other Ontario cities have since soared a further 50% or more.

In June 2016, after Vancouver house prices had shot up over 50% in just three years, I acknowledged that they had entered bubble territory. I pointed to the effect of spillovers from China's aggressive easing of monetary policy on house prices in cities in China and also in cities such as Vancouver and Toronto that are attractive to Chinese investors. I argued, "It is the job of Finance Minister Morneau, along with provincial and city officials, to decide what measures might curb the influence of foreign central bank stimulus on Vancouver and Toronto house prices and how these measures might be applied without bringing about [a] sharp house price correction". In July 2016, Vancouver introduced a 15% Foreign Buyer Tax. In November, the city followed up with a 1% annual tax on the assessed value of vacant houses. Vancouver home sales fell immediately following the introduction of the Foreign Home Buyers tax and prices experienced a moderate setback for a six months before starting to climb again recently.

Toronto's House Price Booms Sometimes End Badly

To read the local newspapers, you would think that Toronto house prices have never boomed before. There are widespread complaints that available housing data are insufficient to determine the causes of the recent rapid price appreciation. But it's not hard to find data that shows that Toronto has been here before. The chart below shows several measures of Toronto house prices dating back to 1969.

The data goes back furthest for the Toronto Real Estate Board average house price (TREB AHP). Also shown are Statistics Canada's Toronto New House Price Index (NHPI) and, more recently, the Multiple Listing Service Toronto House Price Index (MLS HPI) and the Teranet Toronto House Price Index. While the quality of some of these measures is better than others, all of them tell basically the same story. There have been three house price booms in the past five decades in which annual increases reached double digits for consecutive years and peaked at 30% or more.

The first episode, in 1974-75, saw average house prices rise 25% and 30% in consecutive years. In the second episode, in 1986-89, prices rose consecutively by 27%, 36%, 21% and 19%. In the current boom, 2015-17, average prices are on track to rise 15%, 20% and over 30% consecutively.

After the 1974-75 boom, price increases slowed sharply. After the much bigger 1986-89 boom, prices collapsed. The chart below uses the same data as above, but expresses it as drawdowns in prices from their previous peak.

What is clear from this chart is that the drawdown following the 1989 peak was by far the worst house price decline experienced in fifty years. Prices for both new and existing homes fell over 25% and did not hit bottom until 1996, seven years after the boom peaked.

How Did Previous House Price Booms End?

In 1974-75, the boom was ended by a North American recession triggered by the first oil price shock. House prices gains slowed markedly, but there was no crash. Unfortunately, at the peak of house price and rent increases in the runup to the 1975 Ontario provincial election, Premier Bill Davis succumbed to political pressure to invoke strict rent controls. Vince Brescia, past CEO of the Federation of Rental Housing Providers of Ontario describes the outcome:

The results were devastating. Rental housing supply screeched to a halt, vacancy rates quickly began to drop, rents began to rise and tenants couldn’t find apartments. Investors all pulled out of Ontario rentals; they could not operate under a system that incented owners to cut back on investment and let the buildings deteriorate.

The bust in the housing market that followed the 1974-75 boom was concentrated in the collapse of rental housing construction that dragged on for over twenty years and greatly curtailed both the quality and availability of affordable housing in Toronto.

The 1986-89 boom, the biggest Toronto house price surge of the past 50 years, was ended by a combination of rising mortgage rates, a short-lived oil price spike brought on by Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, and another North American recession. After the huge boom, prices plunged and would not recover to their 1989 peak until 2002. Toronto suffered through a lengthy house price deflation in the 1990s.

Eventually, with the election of Conservative Premier Mike Harris on his "Common Sense Revolution" platform, rent controls ended in 1998 on buildings constructed after 1991. This move launched more than a decade of strong construction activity of both privately-owned and rental housing in Toronto that has changed the face of the city.

How Will the Current Boom End?

The current Toronto house price boom is more pronounced than that of 1974-75 but less pronounced and extended than that of 1986-89. The chart below shows the three booms, with the start date set when annual house price gains exceeded 10% on a sustained basis. The horizontal axis shows the number of months from the start of the boom. The prices are in real terms (i.e. deflated by the CPI) to make them comparable.

The chart shows that the current boom has just about matched the 1973-75 boom in duration (at 33 months vs. 36) and that cumulative real price appreciation since the start of the boom has been 55%, about 12% more than at the peak of the 1973-75 boom. However, the current boom has not yet come close to matching the 1985-89 boom in either duration or cumulative real price appreciation.

This implies that the current boom could go on for more than another year and prices could rise by a further 30% without exceeding the 1985-89 boom. However, that may seem unlikely because governments are already taking active steps to cool the market.

The current boom bears more similarities to 1973-75, not only in duration and magnitude, but also in the types of government action taken to cool the boom, influenced by political pressure on an Ontario Premier ahead of a provincial election.

When the two previous booms ended real house prices fell. After the 1975 peak, real prices fell 12% over the next six years. Following the 1989 peak, real prices fell 35% over the next six years. Housing starts also went from boom to bust after the housing price peaks, as shown in the chart below. Following both the 1975 and 1989 peaks, housing starts plunged by more than 40% compared with their level at the start of the price boom.

The current boom lies in between its' predecessors. If we are seeing the peak now, it might be reasonable to expect real prices to decline 15-20% over the next six years. However, as occurred following the 1975 peak, construction of rental housing is likely to fall dramatically and the availability of affordable housing is unlikely to grow.

Of course, if the current boom continues for another year and another 30% price appreciation, it would look more like the 1989 peak. In that event, a deep, long house price recession would become likely and future real prices might then be expected to decline something like 30-35% from the peak.

Some may say that Toronto house prices will never decline. But they have in the past. Ben Bernanke famously said in July 2005, "We’ve never had a decline in house prices on a nationwide basis. So, what I think what is more likely is that house prices will slow, maybe stabilize." That seems to be the hope of the three wise men. But Toronto's history clearly demonstrates that there is a good chance that, like its two predecessors, this boom will end badly.

Canadian economists were quite upbeat on the March labour market report. Headlines from the major banks carried a common theme:

- "Canadian Jobs March On" (CIBC)

- "The Beat Goes On" (BMO), and

- "Canada’s job gains beat expectations again!" (RBC)

Sounds pretty good. But even as the economists purred over the job gains, they noted that wage growth was still quite soft. The reports, as per usual, focused on the minutiae of month-to-month changes in employment across different industries and among full-time and part-time workers, many of which were not statistically significant. It's rare for economists who face the daily grind of reporting on every economic indicator to step back and look at underlying trends inside the labour market. But doing so helps explain some seeming anomalies and overall paints a less rosy picture of labour market.

Hours Worked Tell a Different Story

While employment was up 1.5% in 1Q17 on a year-over-year basis, total hours worked by those employees at their main job was actually down 0.1% (even with a sizeable jump in hours worked in March). Main jobs are the source of the vast majority of Canadians income from work. Some, who cannot make a living wage at their main job, take on second or third jobs to supplement their incomes. Apparently, more people have had to take on extra jobs over the past year, as total hours worked at all jobs were up 1.4% in 1Q17.

When we look at hours worked on main jobs by industry, we find that several key industries with high-paying jobs have seen substantial declines in hours worked, while other industries with low-paying jobs have seen increases in hours worked, as shown in the chart below.

The biggest declines in hours worked over the past year have been in the resource sector, especially in the oil and gas industry. Manufacturing, construction and utilities have also seen substantial declines. Large employers like health and social services and education have seen small declines. At the other end of the spectrum, decent gains in hours worked have occurred in accommodation and food services, transportation and warehousing, business services (which includes waste management) and finance, insurance and real estate. By far the largest gain in hours worked over the past year has been in public services (i.e. federal, provincial and municipal governments).

When one sees these changes in hours worked, it becomes much less of a mystery why wage growth has been weak. According to Statistics Canada's Labour Force Survey, the average hourly wage earned by employees at their main job was C$26.12 in 1Q17. But some industries paid much higher (or lower) hourly wages than the average, as shown in the chart below.

The resource sector, which experienced the biggest decline in hours worked, was the industry with one of the highest average hourly wage rates, over $13 per hour higher than the Canadian average. The utilities, construction, and education industries, which also pay above average wages all saw declines in hours worked. In contrast, the accommodation and food services industry, which pays the lowest average hourly wage -- $11/hr below the national average and $24/hr less than the resource sector -- was one of the industries which saw a meaningful gain in hours worked. The wholesale and retail trade, transportation and warehousing, and business services sectors, which pay below average wages, also saw increases in hours worked. The one anomaly is the public sector, where hourly wages are high and hours worked posted the largest increase of any sector.

It seems clear that Canada is experiencing decent total job growth, but that total hours worked for employee's main jobs have been flat, with high-wage industries reducing hours worked, low-wage industries increasing hours worked. This is not a sign of a healthy labour market.

Why is this happening?

If I had to come up with a story to explain the labour market developments of the past year, it would go like this. The collapse in the world price of oil, which began in mid-2014, resulted in a dramatic declines in hours worked in Canada's resource sector in 2015 and 2016. Declines in energy-related activities spilled over into the non-residential construction, utilities and manufacturing industries. These declines were probably magnified by a tightening of environmental regulations which stalled pipeline construction and carbon tax proposals by governments concerned with global warming. With weakness in key sectors of the economy and new left-of-centre governments in Ottawa and some provinces, hours worked in governments shot up. The sharp weakening in Canada's former industrial growth drivers triggered two 25 basis point policy rate cuts in 2015 and a 20% depreciation of the Canadian dollar relative to the USD. With interest rates falling to rock-bottom levels and the currency cheapening, housing prices in Canada's most cosmopolitan cities -- Vancouver and Toronto -- became extremely attractive to both foreign and domestic purchasers and the real estate industry boomed as the house price bubble inflated. The weakening of the currency made foreign travel more expensive for Canadians, while at the same time making travel to Canada less expensive for foreigners, benefitting the transportation, accommodation and food service industries.

So, while many economists look at Canada's job gains over the past year through rose-coloured glasses, I see the changes occurring in Canada's labour market as signs of weakness in the the Canadian economy. More Canadians are forced to work multiple jobs to make a decent living. High-paying jobs are harder to find. Employment gains are concentrated not in a thriving private sector, but in low paying industries benefitting from a cheap currency, in a bubbly and unsustainable real estate sector, and in activist, meddlesome governments.

The first quarter of 2017 is in the books, so it's time to review the performance of our global ETF portfolios. The quarter kicked off with the inauguration of President Trump and ended with the Trump Administration's failure to win passage of a bill to repeal and replace Obamacare in the House of Representatives dominated by his Republican Party.

Against this background, a Canadian stay-at-home investor who invested 60% of her funds in a Canadian stock ETF (XIU), 30% in a Canadian bond ETF (XBB), and 10% in a Canadian real return bond ETF (XRB) had a 1Q17 total return (including reinvested dividend and interest payments) of 1.7% in Canadian dollars. Had that investor diversified her portfolio to the global ETFs that are tracked in this blog, her returns would have been as much as twice that high.

The weaker performance of the all-Canadian portfolio continues a trend that began with the election of Donald Trump as US President. However, the leading global ETF performers evolved in interesting ways in 1Q17 that reflected, in part, the markets' changing assessment of Trump's ability to implement his election promises.

Global Market ETFs: Performance for 1Q17

The chart below shows 1Q17 returns, including reinvested dividends, in Canadian dollars (CAD), for the ETFs tracked in this blog. The returns are shown for the period from the US election in November through the end of 2016 (blue bars) and for 1Q17 (green bars). As the CAD appreciated 1.1% against USD, two of the best global ETF performers were Emerging Market equities (EEM) and Gold (GLD), each of which suffered big losses in the immediate aftermath of Trump's win. The worst performer in 1Q17 was the Commodities ETF, which had posted sharp gains immediately following the election.

Global ETF returns were mostly positive across the different asset classes in 1Q17. In CAD terms, 17 of 19 ETFs posted gains, while just 2 posted losses.

The best gains were in the the Emerging Market Equity ETF (EEM) which returned a strong 11.3%. The Eurozone Equity ETF (FEZ) was second best, returning 7.7% in CAD terms, followed by the Gold ETF (GLD), which returned 7.1% in CAD. Other solid gainers included the S&P500 ETF (SPY), the Japan Equity ETF (EWJ), and Emerging Market Local Currency Bonds.

The worst performers were the Commodities ETF (GSG) which returned -6.5% and the Canadian Real Return Bond ETF (XRB) which returned -1.6%.

Global ETF Portfolio Performance for 1Q17

In 1Q17, the global ETF portfolios tracked in this blog posted solid returns in CAD terms. However, as with the performance of individual ETFs noted above, the performance of of the various portfolios evolved significantly in 1Q17 versus that of the immediate post election period, as shown in the chart below.

A simple Canada only 60% equity/40% Bond Portfolio returned 1.7%, as mentioned at the top of this post. While solid, the 1Q17 return was weaker than the all-Canada portfolio achieved in the period immediately following the US election and also weaker than the returns on the global ETF portfolios.

Among the global ETF portfolios that we track, the Global 60% Equity/40% Bond ETF Portfolio (including both Canadian and global equity and bond ETFs) returned 3.6% in CAD terms, continuing its strong performance in late 2016 and making it the best performing portfolio since the election. A less volatile portfolio for cautious investors, the Global 45/25/30, comprised of 45% global equities, 25% government and corporate bonds and 30% cash, returned 2.8% in 1Q17, about the same gain it enjoyed in the immediate post election period.

A Global Levered Risk Balanced (RB) Portfolio, which uses leverage to balance the expected risk contribution from the Global Market ETFs, gained 2.8% in CAD terms. This was a remarkable improvement over the return of -0.17% in the immediate post election period, as bonds and foreign currencies performed significantly better in 1Q17. An Unlevered Global Risk Balanced (RB) Portfolio, which has less exposure to government bonds, inflation-linked bonds and commodities but more exposure to corporate credit, returned 2.5%, also a significant improvement over the immediate post election period.

Key Events of 1Q17

In my view, the main events that left a mark on Canadian portfolio returns in 1Q17 were President Trump's setbacks and delays in implementing his election promises; the decision by the US Fed hike its policy rate more quickly than markets had expected; and stronger-than-expected growth of DM economies outside the US.

Trump's setback on Obamacare, as well as the successful court challenges to his executive order temporarily banning immigration from certain countries, demonstrated both legislative and judicial obstacles to implementation of some of his election promises. Markets had cheered his promises to reduce regulation and cut taxes. He has made headway on cutting regulation but the setback on Obamacare has raised doubts about his ability to get controversial elements of tax reform through Congress. In addition, Trump has not yet followed through on his protectionist election promises targeting Mexico and China which had hammered Emerging Market stocks and currencies in the immediate aftermath of the election.

The Fed's decision to hike in March dampened bond prices, especially for longer term bonds. Meanwhile, stronger-than expected growth in the Eurozone, Japan and Canada helped boost equity returns outside the US.

Looking Ahead

At the beginning of 2017, I said that the most interesting question, in my mind, was whether the all-Canada 60/40 ETF portfolio would outperform the unhedged global ETF portfolios as it did in 2016. The answer, so far, is that since the election of Donald Trump the all-Canadian portfolio has returned to the pattern of the past five years, in which it lagged the performance of the global ETFs portfolios by a wide margin.

Three months ago, I said that answer to the question would be determined in part by the behaviour of commodity prices, the Bank of Canada and the Canadian dollar. Commodity prices which were expected to firm modestly, have fallen. The Bank of Canada has so far remained in no hurry to begin raising its' policy rate, even as the Fed hiked in March, sooner than expected. Despite weakness in commodity prices and a dovish BoC, the Canadian dollar, which was expected to weaken moderately against the USD, actually appreciated by over 1%. Upward revisions to expectations for Canadian GDP growth along with President Trump's limited success, so far, in implementing his policy promises has weighed on US dollar sentiment and helped lift the Canadian dollar.

If Trump's plans continue to be thwarted or watered down by Congress, the trends of 1Q17 may be expected to continue. Emerging market equities, bonds, and currencies, which sold off in the immediate post-election period on fears of Trump's promises of protectionist policies, have further room to rally.

The main risk to that outlook is that President Trump, stung by his early setbacks, redoubles his efforts on protectionist trade policies and tax reform, including some form of border tax.

Toyota Motor said will build a new plant in Baja, Mexico, to build Corolla cars for U.S. NO WAY! Build plant in U.S. or pay big border tax. (@realDonaldTrump)

With this tweet on January 5, President-elect Donald Trump got the attention of not only of Toyota and Mexico, but also a few astute Canadians. The realization began to dawn on them that Trump's promise to "Rip up NAFTA" was not the only threat to jobs and investment in Canada. Some may have even realized that the "big border tax", if adopted, could turn out to be a bigger concern than a renegotiation of NAFTA, which the Trudeau government was already contemplating.

One of these astute Canadians, Daniel Schwanen, international trade specialist and Vice-President of Research at the C.D. Howe Institute, when questioned about the border tax by the Globe and Mail, said:

On its face, this proposal is devastating. This could really hurt trade and millions of workers in Canada.

How Did Trump Dream Up the Border Tax?

The so-called border tax is not a trade policy. It is a part of a sweeping corporate tax reform that did not originate with Donald Trump, but with Paul Ryan, the Republican Speaker of the US House of Representatives and Kevin Brady, Chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, as unveiled in their “A Better Way” plan last June. As pointed out by Dylan Mathews on Vox.com, the Ryan-Brady plan,

includes a big cut in the tax rate, from 35 percent to 20 percent. But it also includes some huge changes in the way the corporate tax works... They want to make it impossible for companies to deduct interest payments on loans... They want to make big capital investments totally deductible in the year they’re made rather than “depreciable” over time... But perhaps most dramatically of all, they want to allow companies to totally exclude revenue from exports when calculating their tax burden, and to ban them from deducting the cost of imports they purchase.

Think of how this change would affect US companies that purchase imported goods from Canada (or elsewhere) either as inputs to their own production or for final sales to US consumers. Currently, such imports are a deductible business expense when calculating US corporate taxes. Under the Ryan-Brady plan, the cost of imported goods would not be deductible. The cost of inputs purchased from US domestic companies would be deductible from US corporate tax, providing a huge cost advantage to sourcing inputs from within the United States rather than from abroad. On balance, the result of the corporate tax reform would be equivalent to imposing a 20% tariff on imports from Canada (and other countries).

Now think of how the change would affect US companies that export to Canada where they compete with Canadian companies. The US companies would no longer have to pay any corporate tax on their export revenues. As a result, US companies would either see a large increase in their profit margins on exports or they could cut their prices, thereby forcing Canadian companies to do the same. But Canadian companies would still have to pay Canadian corporate taxes on their revenues.

This would be a horror story for Canada (and Mexico and other major US trading partners). The table below shows Canada's exports to and imports from the United States.

Based on 2015 data, the latest year available, the border tax would be assessed on C$367 billion of Canadian exports to the US. Canada's export-oriented industries – energy, motor vehicles and parts, minerals and metals, and forest products – would be placed at a big competitive disadvantage relative to US-based competitors. At the same time, C$285 billion of US exports to Canada would not be subject to US corporate tax. Canada’s import competing industries – food products, machinery and equipment and other consumer goods – would face much stiffer competition from US exporters that would not have to pay corporate tax.

How US Economists View the Border Tax

Such sweeping US tax changes may seem radical, but they have support from respectable US economists including Alan Auerback of Berkeley, who has long been a proponent of the border tax, and Martin Feldstein of Harvard, who wrote in an op-ed piece endorsing the idea in the Wall Street Journal on January 5, the same day Trump tweeted about the border tax.

Feldstein explains the new border tax with some simple examples. Here is one, with my additions to make the consequences clear for Canada shown in brackets:

A U.S. importer that pays $100 to import a product [from Canada] can, if there is no border tax adjustment, sell that product to a U.S. retail customer for $100. But with the border tax adjustment, the $100 import cost is not deductible from the corporate tax base. The price to the U.S. retail buyer would have to be $125, of which $25 would go toward the 20% tax... This calculation makes it look as if the border tax adjustment causes the U.S. consumer to pay 25% more for [imports from Canada]. But the price changes that I have described would never happen in practice because the [US] dollar's international value would automatically rise by enough to eliminate the increased cost of imports... With a 20% corporate tax rate, that means that the value of the [US] dollar must rise by 25%. [This means that the US dollar would have to rise to 1.67 Canadian dollars from 1.33 currently, meaning that the Canadian dollar would need to drop to 60 US cents]. The rise of the dollar relative to foreign currencies means that the real purchasing power of foreigners declines to the extent that they import products from the United States or sell products to the U.S.

Feldstein explained his view that the US dollar would strengthen quickly to offset the impact of higher import prices for US consumers at this link on Bloomberg TV. You can judge for yourself whether you believe exchange rates would move as Marty asserts. He also asserted that the border tax would raise US$120 billion per year relative to the current corporate tax with the tax burden being borne by US trade partners.

Not all US economists support the border tax idea. Lawrence Summers, former Treasury Secretary in the Clinton Administration and therefore not likely to have may sway with Trump, wrote this in an op-ed in the Washington Post on January 9:

[T]he tax change would likely harm the global economy in ways that reverberate back to the United States. It would be seen by other countries and the World Trade Organization as a protectionist act that violates U.S. treaty obligations. While proponents argue that such an approach should be legal because it would be like a value-added tax, the WTO has been clear that income taxes cannot discriminate to favor exports. While the WTO process would grind on, protectionist responses by others would be licensed immediately. Moreover, proponents of the plan anticipate a rise in the dollar by an amount equal to the 15 to 20 percent tax rate. This would do huge damage to dollar debtors all over the world and provoke financial crises in some emerging markets. Because U.S. foreign assets are mostly held in foreign currencies whereas debts are largely in dollars, U.S. losses with even a partial appreciation would be in the trillions.

What Could Canada Do?

Trump's apparent adoption of the border tax as a tailor-made solution to his election promises to Make America Great Again and to bring back manufacturing jobs to the United States should be the top concern for Canada's new Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland and for Finance Minister Bill Morneau. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who is busy right now engaging with ordinary Canadians in coffee shops across the country, needs to be briefed.

It is less clear what Canada could do about it, if President Trump and the Republican Congress get on board with the border tax. During the Nixon Administration, when the US slapped on a (short-lived) 10% import surcharge, the Pierre Trudeau government sent its envoys to Washington to seek an exemption, but none was given. Obtaining an exemption from a US corporate tax reform would be a tall order even for a government on good terms with the US Administration. Presumably, Canada would need to adopt a similar corporate tax framework to that of the US and seek to have Canadian produced goods treated the same as US produced goods for corporate tax purposes in both countries. That would take a lot of doing.

Another alternative would be to join together with other US trade partners and challenge the border tax at the World Trade Organization. As Larry Summers points out, while the WTO process grinds on, disruption of trade with the US would be severe and retaliation by some US trade partners would be likely.

A final alternative would be to grin and bear it and accede to Marty Feldstein's solution of letting the Canadian dollar weaken about 20% further against the US dollar to keep our exports from getting priced out of the US market. This would mean a further large hit to Canadian's purchasing power and tacit agreement by Canadians to bear part the cost of reducing the US fiscal deficit.